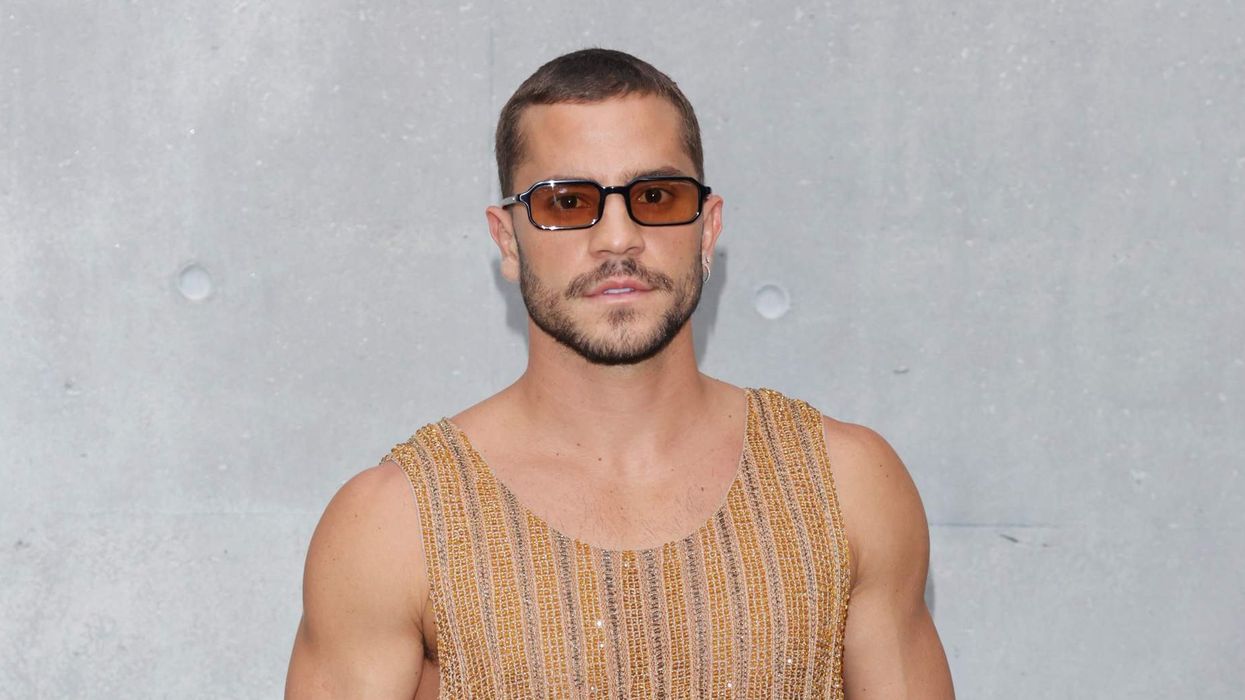

Photography by Alessandro Simonetti

Tye Fortner has fine, delicate ears, a newly pierced eyebrow, and a trim beard. He's wearing honey-colored contact lenses and a Jimi Hendrix T-shirt. "I wanted to be presentable," he explains as a photographer snaps his portrait. "I was going to buy an outfit, but it was so hot."

We are standing outside his apartment block in the Fordham area of the Bronx in New York City on a muggy Friday afternoon in June, a few days before Pride. A woman walks by pushing a wheeled cart from which she's selling Italian ices. "Hey mama!" Fortner calls to her and asks for a scoop of mango and cherry that stains his teeth red. Refreshed, he leads the way up the stairs to the roof of his building, where he takes out a packet of Newports and, perched high above the city, begins to tell his story.

Fortner was 22 and homeless when he started feeling weak, with crushing stomach pain and terrible headaches. A sex worker from the age of 16, sometimes too high on crack to remember to use protection, he had been putting off the inevitable for weeks before he finally decided to get tested for HIV. The result came back positive.

"My whole world changed," Fortner says, recalling the moment six years ago when he received his diagnosis. At first it changed for the worse as he struggled to come to terms with his diagnosis.

But then, it changed for the better.

After years of homelessness and a day-to-day existence, Fortner, now 28, was faced with the tantalizing prospect of a place to sleep, regular meals, and more thorough New York City services provided to people who reach a certain stage of the disease. First he would have to meet their diagnosis requirements; then he would receive help.

"I didn't know about the services," he says. "I didn't know that once you have AIDS you're entitled to all this other stuff."

That silver lining was a surprise to Fortner. And while it might seem counterintuitive, contracting the virus has made life easier for other young homeless men in New York City, who in return for developing full-blown AIDS gain a roof over their heads and basic services.

This cruel paradox -- having to get really sick in order to enjoy a better, more comfortable life -- has not gone unnoticed. "I have experienced people [who are] grateful that they have HIV," says Sage Rivera, a research associate at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention who has worked with hundreds of LGBT youth. "It's sort of like a sigh of relief or an extra boost," he says. "There are a whole bunch of different names for HIV within the [LGBT] community: 'the monster,' 'the kitty,' 'the scratch,' 'the gift that keeps on giving.' So people say, 'I have the kitty -- so now I can get my place. Now I can get hooked up; I can get my food stamps, I can get this, I can get that.'

"Other people say, 'I do not know what I would have done without the monster.' I can think of five boys, automatically, who've told me this."

And it's not just those who already have AIDS who view it as a lifeline; some young men who test negative aspire to contract the disease as a way out of trouble. Rivera knows at least one man who planned to have unprotected sex on purpose, an attitude he sums up thus: "My life is not getting better. I need a helping hand, and it seems like the only way I can get a helping hand is by getting sick."

For Fortner, the phenomenon of young men deliberately contracting HIV is dispiriting but not surprising. "When you're on the streets every day -- winter, summer, spring, and fall -- and you find a way to have an apartment of your own, it looks better," he says. His own experience is instructive: Once his AIDS was diagnosed, he was astonished at how much easier it was to live in New York City. "Right now the rent for my apartment is $1,150, but because I'm on the program I only pay $217, which leaves me with about $400 a month," he says. "That's still a struggle, but I feel gifted, because one way or another I pull through."

Pulling through by contracting HIV is the kind of specter that alarms people like James Bolas, director of education for the nonprofit Empire State Coalition in New York. "It's sad that really young people are forced to take this measure in order to survive," he says, adding that he first heard about young homeless people rationalizing HIV infection as a means to obtain benefits as early as 1987, when the virus was still untreatable.

Nancy Downing, director of advocacy and legal services at Covenant House New York, a youth shelter, has also learned of kids who consider getting infected with HIV/AIDS as a means of survival. "It's bone-crushing," she says. "It's unbelievable that kids have to go those lengths to get the services they need. Young people are sometimes not looking at their long-term future -- they can see only the short-term future -- and that is a developmental issue. It's going to have an impact on them for the rest of their lives. Some might not even take the medication, because at their age -- again, developmentally -- they might not see the need."

Despite the wealth of anecdotal evidence, the New York State Office of Children and Family Services, through its Office of Youth Development --which helps oversee and fund programs for homeless youth -- says it is unaware of homeless gay youth purposely getting infected with HIV/AIDS as a way to obtain services. Meanwhile, the New York City Department of Youth and Community Development, responsible for providing homeless youth in New York City with the services and resources they need to stabilize their lives, would give no comment.

To be eligible for the services provided by New York City's HIV/AIDS Services Administration, commonly referred to as HASA, people must be diagnosed with AIDS or have HIV with certain other specified medical conditions, says Dr. Robert Grossberg, medical director of the Montefiore AIDS clinic in the Bronx. Those eligible for HASA services get a living plan, housing assistance, financial aid, and free medical care. Exactly what each person gets is determined on a case-by-case basis, depending on factors like their income level.

The housing assistance consists of immediate temporary placement in an SRO (single room occupancy) building, which has individual and two-person rooms with shared kitchens and bathrooms, until a permanent apartment is found. Once a permanent apartment is found, HASA covers the rent but residents pay for their own utilities, such as electricity and gas.

In May 2013, HASA was serving 43,845 people, of whom 65.3% were adult men; it also served 156 youth aged 17 and younger. The Bronx has the highest HASA representation of the boroughs, at 36.7%, followed by Brooklyn, Manhattan, Queens, and Staten Island, respectively. Half of those eligible for services are African American, one-third are Latino, and just fewer than 9% are white.

We leave Fortner's rooftop and retire to O'Brien's, an Irish pub a few blocks away. Most of the barstools are occupied by middle-aged Irish Americans watching golf. There are portraits of racehorses on the walls alongside illustrated maps of "Lovely Leitrim," a mountainous county in Ireland. Behind the bar hangs a small brass plaque that reads Sinking ship -- here's the last drink. The bar manager invites us to help ourselves to sandwiches, great doorstops of bread filled with ham and cheese. We play a round of pool as Bruce Springsteen sings "Born to Run" on the jukebox. Fortner is good and wins handily, but his energy is flagging. In addition to AIDS he has epilepsy, and he begins to worry that he might experience a seizure. We head back to his building, taking a route that is familiar to Fortner from his days offering sex for money. A train rumbles above on an elevated stretch of the subway. Fortner points to a 24-hour laundromat. "I used to hang out there a lot," he says.

After his diagnosis, Fortner got so sick that he wound up in a nursing home with four blood clots in each leg, unable to walk for months. "I went from being confined to bed, having my Pampers changed, to a wheelchair to a walker to crutches and then a cane."

One of the ways in which HASA works is that recipients have to have a T-cell count below 200 -- the level at which AIDS is diagnosed -- to be eligible for benefits, encouraging potential recipients to let their health deteriorate to dangerous levels. Fortner sums up his own process of coaxing his HIV into full-blown AIDS as: "Don't take no meds, don't go to a doctor. And that's what I did. I sabotaged myself to get my numbers down."

Fortner also started abusing heroin and crystal meth. "I was doing every drug and my drinking was crazy," he says. He also became more sexually promiscuous: "I kind of slept with anyone and did anything they wanted to do with me."

The plan worked. In 2008 he became eligible for housing, financial aid, free healthcare, and food stamps. Once he reached entitlement he could keep his benefits even if his health improved, so he started taking his pills.

After spending his life in dozens of different houses and shelters, Fortner finally had his own apartment. "It felt like heaven when I walked in," he says. "I'm still in shock that I actually got my apartment. If I didn't have my apartment I would probably still be a sex worker."

Temi Aregbesola was the director of prevention and outreach programs at the Bronx Community Pride Center, an organization that served LGBT youth until it closed in the summer of 2012 due to economic strife. She has often broken the diagnosis of HIV to young gay men, ages 16 and older, and has been shocked by some of the responses. " 'Oh, if I have HIV, I'm good, they will take care of me. I'm going to get housing, I'm going to get my meds,' " Aregbesola paraphrases. "Outside their world, there is still a lot of stigma. But in their world, [it's] 'Oh, I got the monster? This is now an opportunity for me to be better than I was last year.' "

For Johnny Guaylupo, a program coordinator for Housing Works, which connects New Yorkers living with HIV to primary care and social services, the best way to help young people avoid the vicious cycle in which Fortner and others have found themselves is to get them off the streets and into subsidized housing sooner, thereby reducing their likelihood of engaging in risky behavior. Even if they already have HIV, housing can help them live longer. "If you have stable housing, you're able to at least take your medication, eat nutritious meals, get enough sleep, and not go through the stress of living in the streets or having to sell your body," he says.

Since March 2011, Guaylupo has been responsible for targeting homeless LGBT youth between the age of 13 and 24 who are infected or are at risk of becoming infected with HIV. The aim is to link them to emergency housing, medical care, HIV testing, counseling, and other supportive services. They also try to map certain trends. "Are they going out clubbing? Are they doing sex work? Are they doing sex work online, and if they are, where?" he says. The rise of the Internet has moved much prostitution off the streets and onto sites such as Rentboy.com, and although there are no statistics of homeless youth sex workers in New York City, Guaylupo believes it could be in the thousands.

Aregbesola worries that not enough is being done to prevent youth from becoming infected with HIV, and warns that the outlook is getting worse. "A lot of HIV prevention funding has been slashed by the New York State Department of Health," she says. At the same time, HIV infection rates are on the rise. At the end of last year, the CDC issued a report that showed that HIV infection rates from 2008-2010 rose 12% for all gay men -- and a staggering 22% for young gay men. More than half of those (55%) were black men. "It really breaks my heart," says Aregbesola. "It is a chronic illness -- there is no cure. Unless you have some type of magnificent immune system, you will be on meds for pretty much the bulk of your life."

Rivera, too, believes that HIV could have been prevented in those young men who are grateful for the disease if only there had been the resources to reach them. "It could have been if they had had the proper tools, education about what HIV and AIDS is and how it's spread," he says, adding that many young gay men also feel alienated from social programs designed to help them find jobs and develop vocational skills.

Fortner's story is typical of this narrative. "You live in the moment," he says, "and you feel like, I'm not going to be shit, so I might as well just get high and numb everything I'm feeling -- I'm not going to get rescued, this is going to be my reality for life. You really feel that way."

Born in Albany, Fortner was taken into foster care at the age of 14. His parents, addicted to crack, were unable to look after him and his eight younger brothers and sisters. By the time he was 17, he was living in Green Chimneys, a temporary housing center in New York City for homeless LGBT youth. At night he would join up with a group of transgender sex workers, dressing in dark blue skinny jeans, a button-up blouse, and high heels. He painted his face with purple eye shadow and shiny lip gloss and embellished the look with false eyelashes. His purse was filled with condoms and weapons such as a hammer, a screwdriver, and a blade.

"You'd get a lot of assholes that wanted to take advantage of me without paying," he says. "A few times a gun was pulled on me, but you threaten to expose them or call the police, and they either give you the money or take off running." One night he had sex with 14 men. "I could do it without alcohol or drugs, but it was a lot easier to do when I was high or drunk," he says.

In 2007, the Empire State Coalition undertook the first comprehensive study of homeless youth between the ages of 13 to 24 in New York City, and found that, on any given night, more than 3,800 youth were homeless on the streets of New York City, with a fairly even male-female split. Of them, 44.5% were African American and 28% identified as LGBT, with a further 11% unsure of their orientation or uncomfortable answering the question. The number of homeless youth in New York may be higher now, in the wake of a crippling recession. Covenant House's Nancy Downing, for one, claims she has seen an uptick in requests for shelter.

"We have on any given night about 300 youths staying here," she says. "I know that on a monthly basis we get at least 300 inquiries where we cannot respond and provide them with shelter."

State limits mean that young people can stay in runaway and homeless youth shelters for 30 days, and an additional 30 days with permission from the county youth bureau. After that, they are often on the streets again. "When they can't get a space, they're sleeping in Port Authority -- they're finding places to sleep where people can't find them," says Downing. "They're sleeping under bridges, they're sleeping in alleyways, they're sleeping in stairwells."

Even in shelters they can be exposed to danger. "Gang recruitment happens in shelters," Downing says. "Pimps and traffickers also send in young people to recruit. They know that kids are leaving the shelter here, so they'll stand on the corner and try to convince youth that they'll be better off if they engage in prostitution -- they'll have more money in their pockets. It's difficult to identify who's doing what, because the young person who is being sent in here may also be a victim of prostitution and trafficking." By addressing the issues and advising the youth, Covenant House tries to make them more aware of the dangers within their surroundings.

The high representation of homeless LGBT youth in New York City is not surprising to Boris Dittrich, LGBT rights advocacy director for Human Rights Watch. "LGBT youth deal with a lot of discrimination, especially in rural areas of the United States. Once the bullying at home leads them to run away, they all move to the bigger cities," he says, adding that New York needs to focus on prevention. "The education system should focus more on sexual diversity. That's not happening enough, and often is stopped by Republicans and religious groups."

James Bolas, of the Empire State Coalition, acknowledges that Mayor Michael Bloomberg has done more for homeless youth in New York City than former mayor Rudy Giuliani did, but says it's not good enough. "Homeless adolescents are then going to become homeless adults and become a burden on the medical system, the mental health system, the detention system, and the correctional system," he says. "They don't understand that if you can catch and serve effectively from the beginning, you prevent it from taxing society on the end."

The equation is simple, Bolas says: Homeless LGBT youth need the things that anyone needs to live. "To have transportation, to not worry about where their next meal is going to come from," he says. "To have the skills to learn a trade, to earn money. To be able to socialize with people safely and not have to be looking over their shoulders." But the most important thing, according to Bolas, is "to have a place where they can sleep and where their door locks."

Fortner can vouch for that. He still has bad days -- "Sometimes I don't even get out of bed," he says -- but for the first time in a long time he is looking ahead to his future.

Like his idol, Whitney Houston, he sings gospel music in a local church choir and hopes to develop a music career. He is working on getting some headshots, and says he'll dye his hair cinnamon brown to cover some of the marks left by a violent lover who took a crowbar to his head, putting him in a coma for five days. That was back in Albany, shortly before he was diagnosed with HIV and a world away from his life in the Bronx today.

"I kind of created a new family here," he says. "I have a gay father and a gay mother. I met them through a friend of mine and they just took a liking to me. I said, 'You know what? You're going to be my gay mother and you're going to be my gay father.' They've been there for me for years now."

Back at his apartment, he pauses. "I never thought I'd be able to make it here as long as I have," he says. "It's a good feeling." He turns and makes his way slowly up the steps of his building, his home.

Additional reporting by Aaron Hicklin